Opinion: A Personal Take on A Down-Ballot Election

Notes on the 2024 NYS Assembly District 56 Democratic Primary

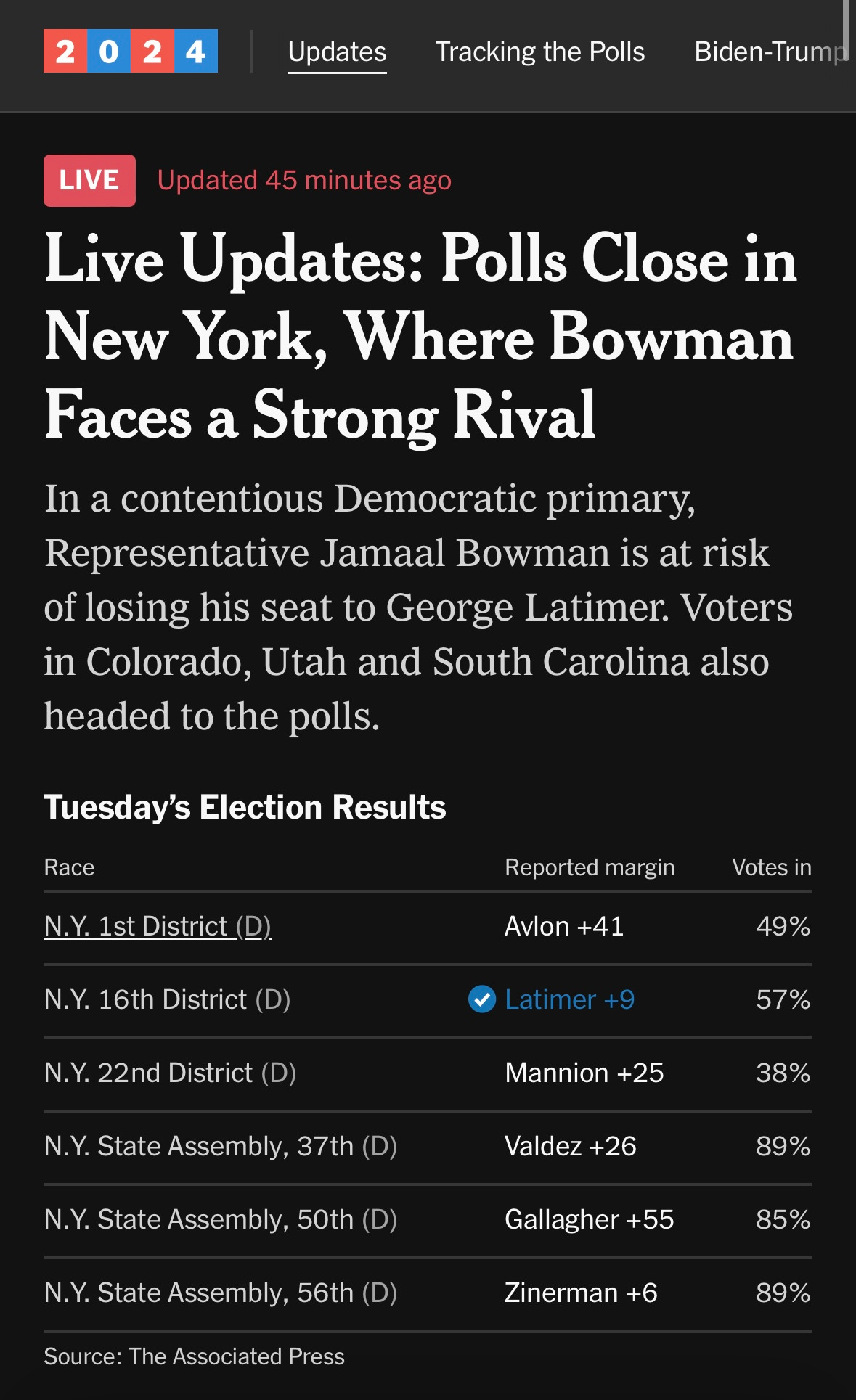

For a brief moment last night, two New York State Democratic primaries were juxtaposed in real time: Congressman Jamaal Bowman’s eventual 16 point loss to George Latimer, and State Assemblywoman Stefani Zinerman’s six point win over her socialist challenger Eon Huntley.

These races, taken together, offer a challenging picture of leftist city politics. I ran in the 2020 version of the assembly race, where I was the left candidate. In a pre-election prognosis earlier this week, Nick Rafter dissected our campaign’s 2020 loss as a “defeat for the left,” caveating that assessment with a disclaimer that “Cohen was white and a transplant to the neighborhood,” while Huntley, the leftist challenger this year, was “a black socialist … and a Brooklyn native.” In other words, better positioned to win a race that that The New York Times and Politico were characterizing as a proxy battle between Brooklyn socialists, led by the DSA, and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries.

Post-mortem analysis of mine and Stefani’s 2020 race was limited to a narrow corner of New York political journalism, but to the extent it was discussed, the consensus then mirrored Rafter’s analysis now: I failed to join the wave of leftists swept into NY state office that year, because I was a white candidate in a stronghold of Black political power.

I suspect that this kind of flattened racial analysis is why the DSA is on a losing streak that continued last night.

Let me complicate the narrative a bit. AD 56 might look like a “DSA stronghold” from the outside, with socialist pols representing the area in both the State Senate and City Council, but Huntley was endorsed only by the aforementioned Senator Brisport, and not Councilmember Ossé. I can’t speak for either officeholder, but it’s notable that one of the two elected officials upholding this bastion of socialism didn’t even endorse, let alone campaign, in the race.

The other complicating factor is the context for the 2020 primary, where I ran as a leftist challenger to the conservative establishment candidate … but not from within the DSA political apparatus. The DSA never endorsed us, even though some leaders within the organization seem to think they did. Perhaps that’s because I’m a dues-paying member, and that my platform - by design - was indistinguishable from that of their 2020 slate. I ran as a socialist, on the program, but without DSA backing. To be candid, I never sought that support. By the early 2010s, I had made personal commitments, through my racial justice organizing, not to join groups that were lopsidedly white and/or male; DSA was still both in 2016, when I started attending meetings.1

Which brings me to how my race factored into the race. In assessing the politics that drove my loss, Rafter notes that, “Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman ever elected to Congress, came from here.” Congresswoman Chisholm is a personal hero of mine, but we should remember that, in the 1960s, she was an insurgent with ideas that were considered radical by the standards of the contemporary Democratic party and its machinery. Now, Black political organizations are that machine in Brooklyn; Assemblywoman Zinerman’s political philosophy is indistinguishable from that of Mayor Eric Adams. That’s how machines work, by design, whatever their color. I’m white, I ran as a critic of that system, and as a candidate with racial privilege, I was able to push boundaries; while much of the Democratic party was wringing their hands about whether “Defund the Police” was too aggressive sounding, my campaign said “Abolish the Police,” explicitly, and still got 43% of the vote against the machine candidate.

When Huntley lost last night with 47%, I was disappointed but not surprised. Unmooring generations of machine power is hard work. It’s helpful to have the DSA political apparatus at your back in that endeavor, but apparently that’s still not enough in a place as unique as central Brooklyn.

Which brings me to a personal note on the word “transplant,” which the one writer used to describe me. He’s right: I was born in New Jersey, and I only started calling Brooklyn home twenty years ago this month. I got married here, got divorced here, and found love again here. Sheila and I rode out COVID together at our house on Dean Street, then we had two kids, one of whom is about to start 3K at a Bed-Stuy public school. I’m a transplant in the sense of a heart transplant, where you move what’s essential somewhere new, and then you survive and thrive, because everything that you love and matters is there.

Raising a family in Crown Heights, specifically, is a constant reminder of the power of racial difference in society, how Black and Jewish communities intersect, and the psychic joy and pain attendant in those interactions. That’s as true in our post-October 7 world as it was in the 1930s, when my grandma Bubby Sylvia was a Brooklyn kid. A hundred years ago her parents were pogrom refugees; they found heart and home in Brownsville, of all places, and this multi-generational family experience has sensitized me to sanitized stories about our community and its politics. My great-grandparents lived alongside other Jews, American Black folks, Afro-Carribean immigrants, Europeans, and yes, even Shirley Chisholm, who was a few classes ahead of my Bubby at the old junior high school on Glenmore Ave.

This kind of multi-generational, inter-racial proximity does not guarantee understanding, though. In fact, it often creates new opportunities to hurt each other. Closeness, though, can offer openings for justice and healing. As someone who has tried to commit himself to those sorts of multi-racial freedom struggles, last night’s election feels like a low point, not just because reactionary forces at AIPAC spent $20 million driving a wedge between Black folks and Jews to oust a sitting Congressman; but also because the DSA, one of America’s most consequential leftist political organs, saw an opponent taking that same AIPAC and real estate money in my neighborhood, then just acted like “same schtick, new messenger” would be a winning approach.

For the sake of not just multi-racial solidarity, but also for the prospects of the left winning races again, I hope we can turn the page on that strategy, and the mindsets behind it.

To be clear, DSA has made strides in racial representation since the twenty teens, so credit where credit is due. My personal work in movements had caused me to become deeply skeptical of predominantly white male political spaces, and that’s just, factually, what DSA was at the time, no shade.